Most fighters with some familiarity with German longsword know Meyer’s cutting diagram; even if their group turns their nose up at Meyer’s “sporting” style, they probably cut their teeth on the diagram. It’s a simple concept of interlocking rings, where in the first iteration, you cut to the upper right quadrant, then the lower left, then the lower right, then the upper left. The diagram allows students to string cuts together, and leads to a number of important concepts.

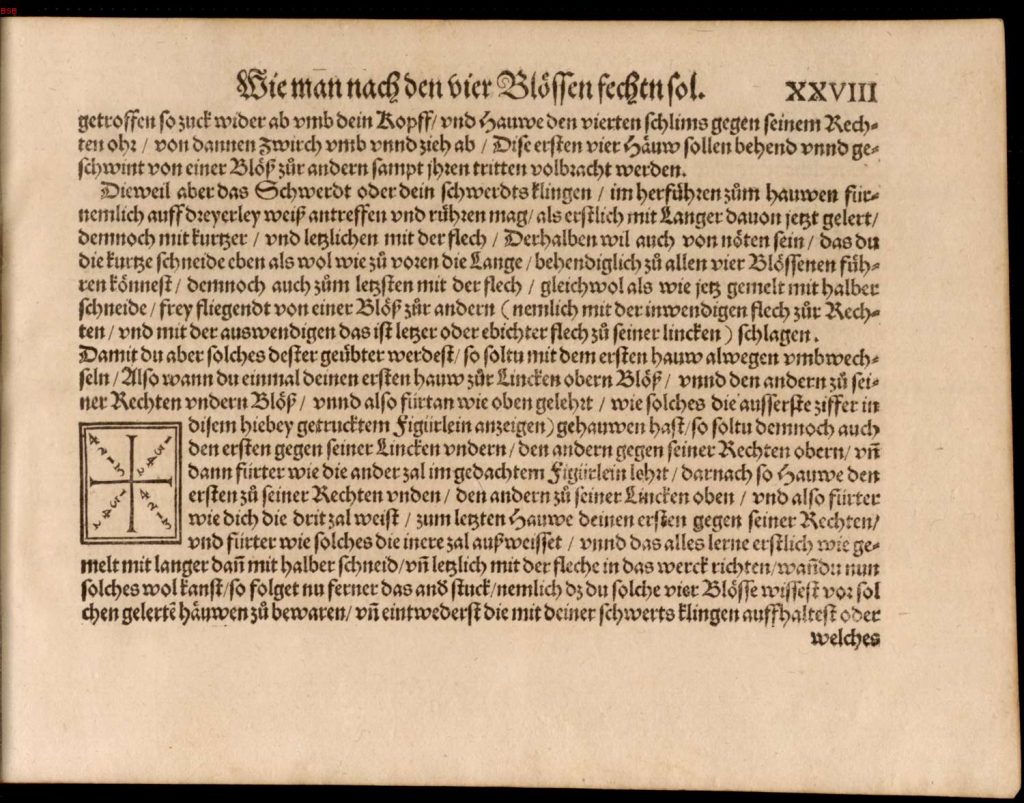

Figure 1: Meyer’s Cutting Diagram, hidden away in the corner of the book

Meyer’s cutting diagram is only part of a large discussion of attacking techniques. It is described in Chapter 10 of Meyer’s Longsword section (Figure 1), where he discusses a number of techniques for use in attacking. I’ve previously written an article about the succession of these techniques in this chapter (https://hroarr.com/article/teaching-progressions-in-meyers-longsword-1-the-attacking-skill-tree/), detailing how Meyer builds from simple techniques like pulling, to feints, to binding and winding. However, Chapter 10 doesn’t actually deal with the most important part of attacking- how to initiate the attack. To understand the process of attacking, we need to look at Chapter 11, where Meyer details numerous “devices” or “pieces” which describe different sequence from different guards.

There are by my count more than 40 devices in Chapter 11 (the exact number depends on how you split some sequences up). Most of these deal with defence, from different starting positions, but about 10 sequences deal with attacking an opponent who does not attack you. These will be the focus of this article, where we look at where Meyer attacks, how he sets up his attack, and how he follows up his initial attack.

So, the devices we are going to look at are detailed in Table 1. I haven’t included some of the final sequences related to the bind (i.e. Mittelhut, Langenort, Brechfenster) because it isn’t clear whether you bind on his sword as a response to an attack, or as an attacking move (I’ll deal with this in another article). Thus, we have a list of 10 devices in which you take the initiative, approximately 25% of the devices in Chapter 11. In terms of the sequence of blows, Meyer follows his own cutting diagram, always moving between diagonally or horizontally opposite quadrants, and throwing in short edge blows and pulls where needed. Where the quadrant attacked is not noted, it can easily be predicted by Meyer’s diagram.

| Table 1: Attacking Sequences in Chapter 11 | |||||||

| Reference (Forgeng) | Starting Guard | 1st Quadrant attacked | 2nd Quadrant attacked | 3rd Quadrant attacked | 4th Quadrant | Notes | |

| 1.32r.2 | Vom Tag | Left Upper (Thrust)1 | Right Lower (Short)2 | Left Lower | Right Upper (short) | Two more strikes | |

| 1.33r.2 | Vom Tag | Horizontal Right | Horizontal Left | Vertical high | Followed by a beat to the sword | ||

| 1.34v.1 | Zornhut | Right Upper | Left Lower | Followed by a slice onto the underarms | |||

| 1.35r.2 | Zornhut | Left Lower | Right Upper (short) | Left Upper3 | Right Lower (Short)2 | Entry via driving | |

| 1.35r.2 | Zornhut | Left Upper (Thrust)1 | Right Lower (flat) | Left Upper (short) | Right (upper) 4 | Followed by a parry and a riposte | |

| 1.35v.2 | Zornhut (L) | Right Lower | Left Lower | Right Lower (short)2 | Entry via driving, attack continues | ||

| 1.36r.1 | Ochs | Right Upper | Left Lower5 | Followed by a parry and a riposte | |||

| 1.36v.1 | Ochs | Horizontal Right (flat) | Horizontal Left (flat) | Continue “as seems best” | |||

| 1.38v.1 | Schlussel | Thrust6 | Opposite side | Continue “as seems best” | |||

| 1.42r.4 | Wechsel | Right Lower (Flat) | Left Upper (thrust)7 | Right Upper | Enter via driving | ||

| Notes | |||||||

| 1 | The quadrant attacked is not described, but since the right hand crosses over left, the left upper makes sense | ||||||

| 2 | I use a Zwerchau coming from below, as per Meyer’s diagram on 1.36r | ||||||

| 3 | No quadrant is described, but Left Upper is prescribed by Meyer’s cutting diagram | ||||||

| 4 | No quadrant is described, but Right Upper is prescribed by Meyer’s cutting diagram | ||||||

| 5 | No quadrant is described, but Left Lower is prescribed by Meyer’s cutting diagram | ||||||

| 6 | No quadrant is described, but the follow up action indicates it can be to the left or the right | ||||||

| 7 | The thrust is delivered with a reversed left hand |

The sequence in which these actions are taught is very characteristic of Meyer, starting with simple sequences tactically, and then moving onto sequences with more decision making.

- In the first sequence, the attacker strings together a long sequence of blows, constantly moving from one quadrant to the next.

- In the second, a preliminary flurry is followed by a beat to the opponent’s blade to open a new line of attack.

- In the third, the initial attack is foiled as the opponent attempts to retreat or counterattack, so the attacker transitions to a slice to the underneath of the opponent’s arms (countering the riposte).

- In the fourth, the idea of driving and crowding the opponent is introduced; the opponent can attack high or low (and be dealt with appropriately), or the attacker can use the driving action to launch an attack from an unexpected angle.

- In the fifth, a second intention sequence is introduced, where the attacker first launches a flurry of blows, then deals with the riposte, and then launches a new attack.

- Ignoring the 6th technique which mirrors the 4th and 5th, we come to the 7th technique which is again a second intention sequence.

- The remaining four devices have less detail, as the attacker is expected to have mastered some skills by that point.

The presentation sequence of the attacks matches with Meyer’s description of the first two of the 4 types of fighters-

“And the first are those who, as soon as they can reach the opponent in the Zufechten, at once cut and thrust in with violence.

The second are more moderate and do not attack too crudely, but when an opponent has fully extended with a cut, fallen low with his weapon, or else has bungled in changing, they chase and pursue rapidly towards the nearest opening.”

“Now as the first ones are violent and somewhat stupid, and as they say, cultivate frenzy; the second artful & sharp;….; so you must assume and adopt all four [attitudes], so you can deceive the opponent sometimes with violence, sometimes with cunning…. “

(Meyer 2.99R, Forgeng translation, page 216).

So, Meyer first teaches us how to use a violent continuous attack against the opponent, then teaches the subtler arts of using an attack to place the opponent at a disadvantage, and apply a second intention attack.

Several other observations can be made:

- Meyer does not necessarily recommend starting with a cut to the right upper quadrant, i.e. an uberhau from high right. Only two devices use this as a starting gambit (1.34v.1 and 1.36r.1), and immediately follow this strike up with an unterhau from below, before moving to either slicing or a parry-riposte

- Meyer uses thrusts to enter in three cases, crossing the hands from Vom Tag and Zornhut, and shooting with crossed hands from Schlussel. The thrust is used to draw a parry, and a blow then delivered from the other side. The thrust could thus be considered a feint.

- Three devices involve approaching the opponent with “driving”, which effectively means swinging the sword continuously, in order to hide the real cut when it comes. In all three of these cases, the starting blow is a cut from below.

- In two unusual sequences (1.33r.2 and 1.36v.1), Meyer advocates using a pair of horizontal blows from each side (right then left) to enter. In the first of these sequences, the pair of horizontal blows is followed by a vertical strike from above; in the other, Meyer advises you to carry on attacking according to opportunity.

- Four of these sequences are actually preparatory, i.e. they create an opening for another technique. In 1.33r.2, the initial flurry is followed by a beat to the opponent’s sword; in 1.34v.1, after the first two attacks, you slice onto your opponent’s arms as he attempts to counterattack; in 1.35r.2 and 1.36r.1, after the initial attack you parry your opponent’s riposte and counterattack. These are thus all “second intention” plays, where you attack in order to draw and deal with a riposte.

In conclusion, an examination of Meyer’s attacking plays in Chapter 11 reveals a lot more of the subtleties of attacking than the more mechanical description of attacking techniques in Chapter 10. Meyer does mount long continuous attacks, but also uses feints, beats to the opponent’s blade, and second intention actions like slicing and parry-riposte action. Some of his attacking plays make use of “driving” as a stratagem, wherein the attacker approaches behind a web of cuts. Many of these strategems would be well known to the swordsmen who followed Meyer, and indeed should be well-known to the modern practitioners of the longsword art.