In Joachim Meyer’s sequence of devices, the principles of hanging and winding are introduced in the second device using the guard of Zornhut (1.34v and 1.35r; Figure 1), immediately after a device dealing with the slice (referred to in my last article). The hanging is also used in a device from the low guard Eisenpfort or “Iron Gate” (1.40r; Figure 2), which offers two options to use from this device. So far in my dissection of Meyer’s devices, I’ve stuck strictly to the second part of Meyer’s text, as I believe it outlines a progressive teaching syllabus. However, since hanging and winding are so important in German longsword, I’ve chosen to supplement these two devices with an extended look at the Low Hanging from the very last section of Meyer’s book (1.63v and 1.64r), as I believe this will provide a more complete picture of hanging and winding in Meyer’s system.

Somewhat confusingly, the act of “hanging” to catch an incoming cut must be differentiated from the guard of Hangetort (“Hanging Point”), an end position for some cuts. Furthermore, Meyer refers to the “Low Hanging” as a hanging above the head (normally done from a low guard, but also from several other positions), and the “inward or high hangings”, which are done from a low bind. This article will focus on the “Low Hangings”, hence forth referred to simply as “hanging”.

Hanging (“hangen” or “hengen”), or the act of catching an incoming cut from above on the flat of your blade, is a very specific form of parrying:

– Hanging is a position where the sword is held above the head, point to the left and hanging slightly down. The thumb is held underneath the sword on the flat of the blade, so the opposite flat is presented to the incoming attack

– The incoming attack is ideally taken on the forte or strong of your sword (portion closest to the hands), which is why the blade hangs down slightly to prevent a blade bouncing onto your hands.

– Ideally the block is done forte to forte (strong to strong), which often necessitates a step forward into the incoming attack

– Hanging is effectively a “block”, a relatively static move, as opposed to the deflecting parries Meyer uses in his devices from Vom Tag (articles here).

– Hanging can only be used to catch attacks coming in at your left or from above; there is no evidence for a “left hanging” in Meyer’s text, or in other German Longsword texts that I know of

– Hanging is intimately tied to winding (“winden”), an action taken while the blades are in contact with one another, in which the pommel is wound out from under the right arm or in under the right arm in order to swing the blade in at the opponent’s head

Figure 1: The second device from Zornhut, detailing how to slide and hang,

and then fight on using the winding in and out

Figure 2: Using the Hanging from Eisenpfort

Figure 2: Using the Hanging from Eisenpfort

Entering the Hanging

In the two devices detailed by Meyer, the hanging is used as a defence from two different guards, the right Zornhut where the sword is held over the right shoulder (Figure 1), and the Eisenpfort (Figure 2), where the sword is held low and pointing forward and down to the left. There are thus two ways of entering the hanging, i.e. using the hanging as a defence.

The first method is relatively simple and intuitive-cross the arms (right over left) and lifting them up over your head, often with a step forward. Meyer in the final part of his book (1.63v) says that this method of hanging can be done from the guard of Pflug or “from the Low Cuts”, which I take to mean the low positions resulting from a descending cut, i.e. the guards of Eisenpfort, Alber, as well as Wechsel and Nebenhut on the left). Interestingly, this is one of only four explicit references to Pflug in Meyer’s Longsword, and the only reference which details an action to be taken from Pflug; one reference (1.6v) describes the guard, and two others (1.53r and 1.56v) describe counters to Pflug. This may also be one of very few implicit references to Alber.

The second method of entering the hanging is to use a technique called “sliding” or “sliding under” (“verschieben” or “unterschieben”), which Meyer describes as doable from all postures but only details as being done from Zornhut. This technique involves lifting the hilt up and sliding the blade over your head and forward into the hanging position. This technique takes practice, but can be done subtlely and effectively against an over-aggressive opponent.

Basic options from the hanging

No defence is any good unless it allows for an immediate counter attack, and the hanging is no different. Two options are detailed in the two devices Meyer describes, and a third option is detailed at the end of the book:

– The attacker’s blade may deflect off to the left, giving you the opportunity to attack in immediately. In my own group, a short edge cut from above is often used as our counter of choice in this situation.

– The attacker may immediately pull his blade away from the block, possibly even before the blades clash. In this case, Meyer exhorts you to immediately chase his ascending blade with cuts from below, forcing him to parry and expose his head. This is a type of “chasing” or “nachreisen”, and can be very effective.

– As the blades clash, you can wind your short edge in at your opponent’s head, entering the “Krieg” or “War” portion of the fight

The winding in

The winding is a characteristic technique from the German school of longsword (and messer), but it is a controversial technique, with varying interpretations out there. There are also different uses for the winding in early German longsword (e.g. Ringeck and contemporaries) and later sources such as Meyer and Sutor (some sources intermediate between the two such as Mair may show the full spectrum of options). Meyer’s winding is used to deliver a strike with the short edge or the flat to the sides of the head, whereas the early German longsword school used the winding to line the point up for a thrust, leading to a lot of debate on how and what the winding actually is. In this article, I’ll stick strictly to Meyer’s description of the winding and leave the debate on early vs. late winding differences to other fora.

At its core, winding involves rotating the right arm (assuming a right handed fencer), either from fingers down to fingers up or vice versa. As the right arm rotates, the left hand steers the point of the sword by either pulling the pommel out from under the right arm, or pushing the pommel in under the right arm. The thumb is used to turn the flat to align the edge with the opponent.

Winding can be subdivided into “winding in” and “winding out”, two mirror image techniques used to deliver two blows to the same side of the opponent’s head, to the upper and lower openings on the head. Defining which is which is often confusing, as the actions will use a different combination of movements when done from the left (from the Low Hanging) or from the right (from the High Hanging). I normally define the first movement, to the upper head opening, as “winding in”, and the second movement, to the lower head opening on the same side, as “winding out”. Another way of thinking about it is that “winding in” involves pointing the thumb towards the opponent, and “winding out” involves pointing the thumb away from the opponent.

If we look at the hanging specifically, the action of winding in can be broken down as follows:

– The blades clash forte to forte, your blade below his. Your right thumb points to the left, palm faces down

– You rotate your right arm so your thumb points towards your opponent. At the same time, you pull your pommel out from under your right arm, and turn the edge of your blade using your thumb so your thumb ends up on top of the blade

– As you do this action, you should lift your opponent’s blade over your head and strike his right ear with your short edge. You can help protect your head by pulling to the left.

Meyer describes this action as resulting in the position shown in Plate L (figure 3), though I don’t think this image is particularly useful, as the opponent is shown in an unusual position. Therefore I’ve taken two pictures showing the winding as I do it (figures 4 and 5). Hopefully they are useful, despite my inelegant attire!

Figure 3: Centre scene in Meyer’s Plate L. The fencer on the right has wound in from the hanging, but the figure on the left doesn’t match Meyer’s text.

Figure 3: Centre scene in Meyer’s Plate L. The fencer on the right has wound in from the hanging, but the figure on the left doesn’t match Meyer’s text.

Figure 4: James catches Chris’s attack with a hanging

Figure 5: James winds in at Chris’s head. Note the hand change from Figure 4

Figure 5: James winds in at Chris’s head. Note the hand change from Figure 4

Winding out

After the winding in, the ideal situation would be that the opponent has been struck in the head. However, this need not be a fatal blow, or the winding could miss and go over the opponent’s head. Thus, the winding in is normally partnered with the reverse action, referred to as winding out. In this action, you hold the short edge against the opponent’s blade and lift it to your right (as shown in Meyer’s Plate F, figure 6). At the top of the wrenching, you push your pommel back in under your sword, so the point swings down and in at the opponent’s head, striking the opponent with the inside flat from below at his right cheek.

Figure 6: The fencer on the left has wound in, and now wrenches the opponent’s blade up to the right. From here, he will push his pommel under his right arm and wind out at the opponent’s head

Figure 6: The fencer on the left has wound in, and now wrenches the opponent’s blade up to the right. From here, he will push his pommel under his right arm and wind out at the opponent’s head

The last portion of Meyer’s commentary ((1.63v and 1.64r) also refer to using the winding out as a response to the opponent attempting to “rush downwards from above to the opening”. I take this to mean that if the opponent pulls his sword away during the winding in, you immediately wind out to prevent him striking your exposed right side.

In Meyer’s device from Zornhut (figure 1), the winding out is followed by the Clashing Cut (Glützhauw), basically a beat with the flat from the right to the opponent’s sword, clearing the way for a short edge cut from above to the opponent’s head.

The Winding Through (Durchwinden)

The device from Eisenpfort (Figure 2) offers a different follow-up to the winding in. Instead of winding out, you can instead “wind through” by pushing your pommel under your right arm while stepping to the right, basically moving under your opponent’s sword. This movement is lead by the pommel, pushing it through under your arm and up to your right, letting the point drop to the left and freeing your blade from the bind.

In the device from Eisenpfort, Meyer tells us to follow the winding through with a long edge cut to the opponent’s head, making space for this cut by stepping back. A second option is presented in the end notes (1.64r), in which you catch over the opponent’s left arm with your pommel as you wind through. From here you can wrench down to yourself, and strike the opponent in the head with your edge.

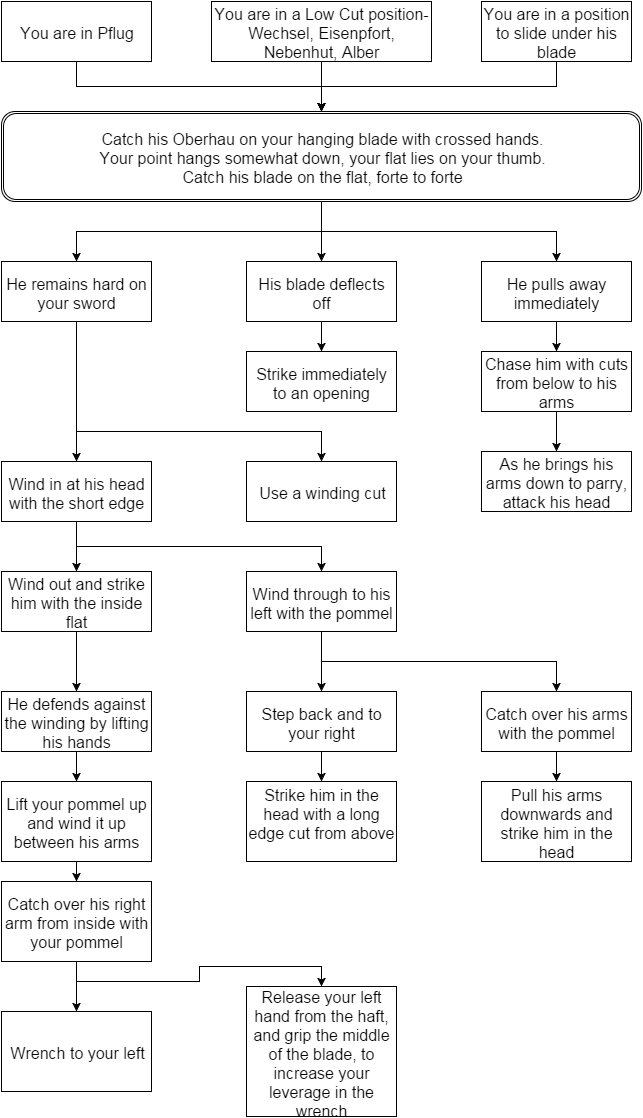

Putting everything together

It is possible to put all the information about the hanging into a single flowchart, incorporating not only the techniques detailed in the devices from Zornhut and Eisenpfort, but also some additional techniques detailed in Meyer’s end notes. This can be seen in Figure 7.

Figure 7: The complete decision tree from the hanging

Figure 7: The complete decision tree from the hanging

Two new techniques are detailed in the end notes which are not used in any of Meyer’s devices:

– The Winding Cut (Windthauw) is done from the hanging. In this technique, the pommel is pulled out from underneath the right arm, and the point swings in over the opponent’s head in a loop, and you strike the opponent’s head over his right arm and behind his sword (Figure 8). In doing this, the head needs to be pulled away from the opponent’s sword, out to the left. This technique must be done quickly, and uses surprise for its effectiveness.

Figure 8: The big figure on the right is using a winding cut on the opponent to the left.

Figure 8: The big figure on the right is using a winding cut on the opponent to the left.

– The second new technique is a very interesting one. One possible way to defend against the winding in and out is to lift your arms, effectively entering into your own hanging. This can be followed up with winding through. If your opponent defeats your winding in this way, then Meyer tells us to lift the pommel up between his arms, hook the pommel over the opponent’s right arm from inside, and then wrench him down to the left. A second variation involves releasing your left hand from the hilt as you hook over the opponent’s arm; you can then grip the middle of your sword with your left hand, in order to increase your leverage in the wrench.

Concluding comments

It’s interesting that Meyer first teaches the windings from a hanging, as opposed to a more common bind such as Pflug or Langenort (i.e. the swords bind right to left, point up). In many respect, the only option from the Hanging is to wind, whereas numerous other techniques come naturally from the normal bind. Meyer leaves the winding from the normal bind for later in his devices, possibly indicating that he finds it more difficult to teach the windings from the lower bind. I definitely find it easy to introduce winding with the hanging, as students have to step into the oncoming attack with their Hanging, leading to a natural aggressive flow.

The hanging and winding is an elegant set of techniques for use in the bind. The devices from Zornhut and Eisenpfort are a good introduction to the “Krieg” or “War”, an important part of the German school of longsword. Though Meyer’s windings are used for a different purpose than those in the earlier German sources (to strike the opponent rather than to line up a thrust), they are still extremely effective in a fight. However, there are a myriad of counters and options from a hanging, and it takes a lot of practice to pick the right option, based on the opponent’s actions. Since the swords are bound together and the distance is short, much of the decision-making in the bind must be made from the “feeling” or “fuhlen” on the blade, which takes time to learn.